Solstice Park is “a strategically located development opportunity”. That’s what its promotional blurb says, anyway – but put more prosaically, it is a clump of offices, distribution centres and retail and hospitality businesses on the A303, just under 10 miles from Salisbury. It symbolises two things: government attempts to help the economy of south-west England, and the tourist industry centred on Stonehenge, a few minutes’ drive away. As if to somehow complement the monument’s antiquarian wonders, there is a faux-ancient statue outside the Holiday Inn, of a 22ft figure giving thanks to the sun. Inside, double rooms go for just short of £100.

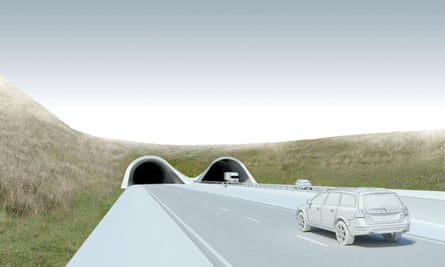

It’s 8am on a misty Wednesday morning and a group of people here are very anxious about the latest proposal for this historic patch of England: a 1.8 mile tunnel containing a new dual carriageway, its entrance and exit sitting inside the Stonehenge world heritage site, and which may also involve a new flyover. After years of proposals for a tunnel being knocked back and forth – a similar plan was ruled out in 2007 – the latest scheme was announced by then chancellor George Osborne in 2014. Soon after, David Cameron and Nick Clegg staged separate photo opportunities on the same day at Stonehenge, in an attempt to sell the economic benefits of a tunnel and widened road to locals. Give or take consultation processes and concerns about the costs, work is due to start in 2020.

The government talks about a supposed reduction of the congestion that has long affected this part of Wiltshire, and an upgrade that will “develop the A303 into a high-quality, high-performing route linking the M3 in the south-east and the M5 in the south-west, improving journeys for millions of people.” Both English Heritage, which runs Stonehenge as a visitor attraction, and the National Trust, which has a stake in Stonehenge thanks to the 800 hectares of land it owns around the stones, are in favour of the plan in principle. They talk about an end to the spectacle of the stones being spoiled by passing traffic, and how the grassing-over of the existing A303 will mean the restoration of the Stonehenge Avenue, the ancient processional route to the monument.

All this might sound reasonable, but there are mounting concerns about what a tunnel will mean, particularly for archaeology in one of the world’s most important prehistoric sites. Twenty-one renowned archaeologists who know the area have announced their opposition. One of the most vocal opponents is classical historian, writer and radio presenter Tom Holland.

Over a Holiday Inn breakfast, he tells me what he thinks is at stake, why the Stonehenge site has to be thought about as much more than the stones, and why a campaign group called the Stonehenge Alliance is making such a lot of noise.

Most obviously, there is a fascinating archaeological site nearby called Blick Mead, where recent finds have shone light on life in the immediate wake of the ice age and why Stonehenge – even before the stones – was a regular gathering-place for people from all over ancient Britain.

If the road plan materialises, Holland says, it will ruin Blick Mead, and bring important work there to an abrupt end. He is also concerned about land close by, where a network of ancient burial mounds and other sites are rich with historical interest. Not to mention the fact that the planned site for one of the tunnel’s entrances (or “portals”) threatens one of Stonehenge’s most significant aspects: the direct line of sight from the stones to the setting sun on the winter solstice.

“The issue is whether Stonehenge exists to provide a tourist experience, or whether it is something more significant, both historically and spiritually,” he says. “It has stood there for 4,500 years. And up to now, no one’s thought of injecting enormous quantities of concrete into the landscape and permanently disfiguring it.”

He is evidently pretty angry.

“I am angry about it, yes. Because if everything mysterious and evocative and ancient is packaged up in to a heritage visitor experience, and sliced and diced, and subordinated entirely to the needs of the road-building programme, there’ll be nothing left.”

Having left Solstice Park, our first port of call is a large expanse of land peppered with bronze age burial mounds and circular burial sites known as disc barrows. It sits in the middle of Boreland farm, a 300-acre expanse owned and run by Rachel Hosier, who drives us around in her Land Rover. In the middle distance a handful of Highways England vehicles flit around the landscape, occasionally disgorging people in hard hats and hi-vis jackets. After a five minute drive through the fields, we get out at a burial mound known as Bush Barrow, which was first excavated in 1808. The finds here were centred on the remains of a man who had been buried along with grave goods including an axe, two daggers, and items of jewellery.

Hosier claps eyes on the nearby vans and diggers, and points out where one of the tunnel’s portals is planned to be built, around 300 yards away. “I’ve grown up with this place,” she says. “My garden just happens to be bigger than other people’s. And I feel very honoured to be a custodian of this land. It’s fascinating. But I’m extremely worried. Bush Barrow man is going to be looking at a tunnel and a big road, right from his grave.”

Half an hour later, after another rendezvous in the nearby town of Amesbury, we head to Blick Mead. So as to protect it from unwanted intrusion, the exact location of this site – a boggy, wooded spot, named after a local farm worker – is a secret. Nearby is a spring that releases water at a constant 10–11C, even when the surrounding land is frozen – which probably explains why human beings were here a long time before Stonehenge was built.

Such animals as aurochs, a huge ancestor of the modern cow whose carcass could feed 200 people, gathered close by, which in turn drew people who used them as a source of food. And the fact that the moist soil here acted as a perfect preservative has meant that items which explain how these humans lived could be excavated up to 7,000 years after they were dropped into the soil.

Over the last 15 years, the prime mover behind archaeological work here has been David Jacques, an expert on the Mesolithic period (8500-4000BC) based at the University of Buckingham. Last year, he and his fellow archaeologists found a 7,000-year-old dog’s tooth, which amazingly detailed analysis suggested may well have been born in the east of England, before being taken to Scotland and then travelled all the way to Salisbury Plain. What this revealed, he says, is how important the Stonehenge area had been long before the circle itself was built. He has also been working on the remains of an ancient dwelling in Blick Mead, which offers clues about both visitors to Salisbury Plain, and people who lived here on a more permanent basis.

The proposed eight-metre flyover that would feed traffic in and out of the tunnel, Jacques says, would sit only a few hundred yards away. The concrete would dry out the very moist soil here and obliterate its archaeological richness. “It’ll take down the water table, and if that water table drops, it’ll remove all of the organics, like the animal bones. They’ll all be gone within five years. They’ll be reoxygenated, and they’ll degrade fast. So we’ll lose dating evidence, all the ways of understanding how people were living, and what their resources were.”

And in terms of the bigger historical picture, what would that mean? “We would lose the backstory to Stonehenge. This is genuinely exciting, so it doesn’t need any hype: the house is dated around 4000BC. That is really important, because there’s hunter-gatherer material in there, at the same time as there’s the first Neolithic date at Stonehenge. So simply put, you’ve got the first multicultural society here. This is probably a contact point between early Neolithic pioneers coming in from continental Europe, and the indigenous people who had been doing stuff for 4,000 years. Before our site, there was virtually no evidence of Mesolithic occupation in this area at all.”

“Up to now, the assumption has been that Stonehenge was a kind of Neolithic new-build, in an empty landscape. And of course, the big question is: why is it where it is? Nobody’s had a very good answer for that. But now, all of a sudden, we’ve got the longest spread of radio-carbon dates from the Mesolithic of anywhere in Europe. Something really odd was going on: these are normally nomadic people, but they are coming back here again and again and again.”

Half an hour later, we are joined by Andy Rhind-Tutt, a former mayor of Amesbury who is president of the local chamber of commerce. He does not buy the idea of the changes to the A303 as a bringer of local economic benefits (“It won’t bring business to the area – it’s about an expressway to send traffic faster to other parts of the West Country”), and says the fact that the new road will meet a junction leading to the Stonehenge visitor centre will still cause plenty of congestion. “You’ll end up with a traffic jam underground,” he says. “The tunnel will become, effectively, an underground car park.

“And a tunnel won’t deal with the issue of what happens to the traffic when there’s a problem,” he continues. “In fact, it’ll make it worse. A tunnel with a blockage will force cars to come through Amesbury or the local villages, which are already suffering. You’re going to end up with lorries coming through the villages every time the tunnel shuts.

“So the question I have is: What is the purpose of the tunnel? As far as I can see, there’s only one purpose, which is to remove the view of the stones from the road, and remove the view of the road from the stones. There can be no other reason.”

The views of the bodies who support the tunnel plan are inevitably very different. A spokesperson for English Heritage says that “there is still much work to be done on the detail,” but the proposals “have the potential to transform and enhance the landscape”. Nonetheless, they express serious concern about the proposed location of the western end of the tunnel.

At the south-west office of the National Trust, assistant director Ian Wilson says he understands the significance of Blick Mead, and has faith that the road-builders will respect its importance. “What we would expect is that with any works carried out as part of the road scheme, the potential impact on Blick Mead should be assessed, and if there was going to be an impact on the water table, that would need to be mitigated.” He says that Highways England needs to “take Blick Mead into account”. Asked what a new road and flyover would mean for the painstaking archaeology happening nearby, the organisation gives a somewhat gnomic reply: now that the latest public consultation has finished, Highways England is “considering all information and feedback we have received”, and “until we have fully assessed this information we are not in a position to comment further at this time”.

Holland and the Stonehenge Alliance say they would be comfortable with a much longer tunnel, on the proviso that it caused “no further damage” to the world heritage site – and the government’s failure to consider such an area shows that short-term financial considerations are taking precedence over damage that would be irreversible. And they still see glimmers of hope, even if they are often somewhat obscured by clunky acronyms.

The International Council on Monuments and Sites, which advises world heritage body Unesco, said recently that the current design would have a “substantial negative and irreversible impact” on the Stonehenge site, and that consideration has to be given to an alterative route that would take the A303 through land owned by the Ministry of Defence.

Back at Solstice Park, I ask Holland how he feels about the tunnel plan actually coming to pass. “I feel a deep psychic sense of distress at the prospect, to be honest,” he says. “I try to think it’s not going to happen. I absolutely haven’t given up. I think there’s a dawning realisation among the general public that a monstrous act of desecration is brewing. I hope that there will be international disapproval of this: I hope that matters. The government is already quite unpopular abroad; I don’t think it wants to tarnish its reputation any more.”

But what if work actually starts? Would he lie in front of diggers, or take up residence in a tree?

“I don’t know. I’ve wondered about that, and whether I’d be prepared to do that. I’d reserve judgment on that.”

So he might?

“Yeah, I might.”

He thinks for a moment. “If you’re trying to defend a prehistoric landscape that has Stonehenge at the heart of it, there is a kind of poetry and magic to that, which I think would serve as a lightning rod for a lot of people’s anxieties about a lot of things. Ultimately, it’s about whether the government thinks it’s going to damage its reputation. That’s really what it comes down to: is the government going to be anxious about looking like vandals?”

A303: a deathtrap for deer, badgers and foxes

By Stephen Moss

Like many people, I have a love-hate relationship with the A303 – the road due to be bypassed by the controversial Stonehenge tunnel. As my main route from London to my home in Somerset, I love heading westwards on a fine summer evening. But as soon as I reach Stonehenge, the traffic grinds to a halt.

Time, perhaps, to leaf through Tom Fort’s rather optimistically titled book A303: Highway to the Sun. But maybe he will now need to rename it A303: Roadkill Hotspot. For despite the (usually) slow-moving traffic, it seems that the road is just that. With more than 420 animals killed in just over a year, this is the road to hell for deer, badgers and foxes – and even the occasional otter.

But could there now be light at the end of the tunnel? By digging underground, will the highway engineers be able to put an end to this wildlife carnage? Or might it just transfer the problem a mile or two down the road, so that as cars emerge from the tunnel they mow down the wildlife there?

Anyone who lives in the countryside, as I do, is used to seeing the corpses of animals flattened across the tarmac of our rural lanes. It’s a good way to judge the state of Britain’s wildlife, or perhaps its stupidity. Badgers and pheasants appear to be the main victims, while hedgehogs – now as rare as hen’s teeth in my neck of the woods – are few and far between. With this in mind, the Project Splatter website, a citizen science research project at Cardiff University, wants us to report any roadkill sightings to work out what impact roads are having on our wildlife. Judging by the carnage along the A303, the answer is “quite a lot”.

The author is a naturalist, writer and broadcaster who also lectures in nature and travel writing at Bath Spa University

- This article was amended on 26 April 2017. An earlier version used the word “de-oxygenated” where “reoxygenated” was meant.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion