A step up to a restaurant and no threshold ramp in sight. A pub with its function room upstairs, making attending a friend’s birthday drinks impossible. A kerb that hasn’t been flattened, essentially imprisoning you in the road.

To a wheelchair user, such as myself, some cities can feel like no-go areas. Moving around Durham and its seemingly endless cobbles and hills can be a nightmare for people with mobility problems; it’s the same in Bath. And I have spent years paying £40 for a taxi ride when working in central London because the tube is still largely inaccessible to wheelchairs. In Brighton, with its narrow lanes and frequent steps, I often can’t find a suitable restaurant.

It’s the same the world over. Disabled tourists must often pay over the odds for accommodation because they need large, wheelchair-accessible rooms; Paris’s enormous kerbs are a menace. And eight out of 10 disabled people say they struggle when holidaying in the UK, according to research by the Leonard Cheshire Disability charity published this month. It highlights issues with everything from finding accessible hotel rooms to access to bars, restaurants and sightseeing spots.

So when Chester was crowned the most accessible city in Europe this year – the first time in the seven-year history of the Access awards that a British city has been named – it came as something of a shock. The ancient city, famed for its extensive Roman walls and Tudor-style half-timber shopping quarters, is perhaps not an obvious contender for modern disabled access.

“We’re not a city that has suddenly said: ‘Let’s make this accessible,’” says Graham Garnett, access officer at Cheshire West and Chester council, and the architect of the Access award bid. “It has been a commitment over many years.” He says it was this long-term approach that caught the eyes of the European judges rather than any big new developments.

But with the accessible overnight tourism market now worth £3bn (and day visits bringing that figure up to £12.1bn, according to Visit England), it’s clear that investing in accessibility is a prudent marketing decision. The “purple pound” generally is worth £212bn a year.

Chester can afford to make the investment. The prosperous city bustles with cafes and high-end shops. The famous walls alone – two miles of Roman, Saxon and medieval fortification that surround the city – have seen an annual investment of £500,000 since 2009.

In my wheelchair, I find I can easily gain access to the walls. A slope and short passageway lead to what feels like a rooftop walkway, lined with autumnal trees and cushioned by nature and history. Though the camber occasionally lurches me sideways, I do not, to my relief, go crashing into the light railings, taking out the falconry and cathedral on the way down. The entire wall area is impressively wheelchair accessible. Where that isn’t possible for heritage reasons, tactile paving and additional handrails are there for people with visual impairments or mobility problems.

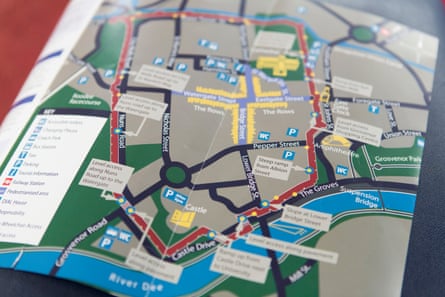

From here, wheelchairs are able to access the Rows, Chester’s unique elevated walkways above its four main streets, which have enabled “double level shopping” since the 13th century – and are now 100% suitable for wheelchairs. It’s a rabbit warren of access. Seemingly hidden passages, filled with fairy-light-strewn cafes, emerge almost magically into the high street. In total, wheelchair users now have six access points to the Rows and 11 to the walls.

There are also tour guides, city centre access guides, signs and online help via the DisabledGo website. The two-tier shops and medieval atmosphere would impress anyone, but it feels particularly novel as a wheelchair user, and it seems fitting that the access has developed over time: the street-level entrances have been there for more than 100 years; ramps were added a few decades ago; a lift in a department store then gave even more access.

But it’s the seemingly mundane aspects of disability inclusion – transport and toilets – that probably gives Chester the edge over its competitors. All of the city’s public buses are fully accessible. Council policy requires all of its licensed taxis to be suitable for wheelchairs. They must also include additional features, such as induction loops and colour-contrasted grab handles. The city has seven Changing Places toilets, which include hoists and a changing bench for disabled people who can’t use standard accessible toilets. And there’s a council commitment to include one in any future renovation throughout the city. “Speaking to other [nations’] reps at the award ceremony, they were so impressed,” Garnett says. “Other cities in Europe don’t have that.”

As well as having a designated access officer since 1991 – a rarity in a climate of council cuts – Chester has had a corporate disability forum, where 16 disability organisations can challenge architects and developers about access plans. The recent £38m renovation of Storyhouse – the new cultural centre, which includes a cinema, theatre and library – had disability access at its heart. It even has an accessible backstage for disabled performers.

As part of the planning permission for the Northgate development, which will include shops as well as leisure and cultural facilities, hoteliers are required to provide two rooms with ceiling track hoists; they will be Chester’s first.

A visit to Chester zoo confirms its well-thought-out access: there is free entry for personal assistants and free disabled parking, as well as multisensory experiences for visitors with visual impairments and advice for those on the autistic spectrum (such as guidance on finding quieter times to visit). I’m able to see the animals from accessible viewing areas – lowered fences with transparent screens – and use a lift to access the tree-high “realm of the red ape”.

And yet, for disabled people, the difference between being able to visit a place and not often comes down to seemingly small details. Garnett tells me of a conversation with a tourist who wanted to visit the zoo, but wasn’t able to because she couldn’t find a hotel nearby with a ceiling hoist. “I investigated it and we didn’t have any in Chester. But they informed me there wasn’t one in Liverpool either. Or Manchester,” he says. “The nearest hotel with a ceiling track hoist was in north Wales.”

In fact, the toughest competition in the accessibility stakes isn’t in the UK. Rotterdam, the runner-up for the award, has paid detailed attention to making public spaces accessible, ensuring walking routes have an unevenness no greater than 3cm, and encourages people to report problems by phone or online. Under its “rapid repair” scheme, the city will fix urgent complaints that affect access within 24 hours. It even boasts a wheelchair-friendly path to the high-water mark on the most accessible beach in the Netherlands.

Axel Dees, the spokesman for Rotterdam’s access bid, cites a willingness to work with different partners across the city, as well as knowledge of disabled people’s needs as vital components to their success. “Accessibility is for, and from, everybody,” he says. “We build our city together.”

The third-placed city, the Latvian spa town of Jūrmala, mirrors many of Rotterdam’s innovations. An 850-metre-long accessible trail links the city with the seaside, while reclining chairs and special wheelchairs for swimming are available on the shore. The city also provides tandem bikes for blind people and beach table tennis that features audible balls.

It isn’t only leisure facilities that impressed the judges. Skellefteå, a coastal city in northern Sweden, was given a special mention for its commitment to improving the working environment for disabled people. “For many years, access to work has been among the top political priorities in Skellefteå,” says Alexandra Sundberg, the municipality’s accessibility coordinator. “We have joined officials from several different authorities under the same roof to make it easier to support those far from the labour market, many of whom have a cognitive challenge.” This approach starts early: the city’s playgrounds have been upgraded to ensure that they can be used by all children, and young disabled people get priority for summer internships.

Chester, however, is not yet a disability utopia. The decking around the zoo is so bumpy for my wheelchair I feel seasick at one point. And after I head through the Roman gardens (a public park created to display a collection of Roman artefacts) and down a winding ramp to the Groves for a 30-minute boat cruise on the river Dee, I find I can’t get down the boat’s steps to the bar. But friendly staff ask – twice – if I would like anything, and a transportable ramp enables me to get on to the deck, a real rarity with a wheelchair.

The award has placed Chester firmly on the accessibility tourism map: Garnett says “disability tsars” across Europe are now coming to visit the city. “We’ve had them from Dublin to Israel,” he says. “They want to see how it’s done.” And as I go through the city, I’m struck by a unique feeling: I’m being included – like anyone else.

Guardian Cities wants to hear from readers with a disability about their experiences of accessing cities – good or bad. Share your experiences here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion